Term 4 Hot Topic: Restorative Justice

‘…we seek to be heard’

Uluru Statement from the Heart

Hello and welcome to our final newsletter for 2023.

In this issue we’re putting the spotlight on an idea that is central to the Uluru Statement from the Heart and relevant to our work with young people: restorative justice.

The Statement sets out a process of representation (The Voice), truth telling (Makarrata) and agreement making (Treaty) to address current and historical wrongs suffered by Indigenous peoples. These wrongs should be heard, acknowledged and justly responded to.

1. Justice beyond the 2023 referendum vote

As educators, our work remains as it was before October 14: to help a generation of non-Indigenous young people grow into adulthood with a compassionate, empathetic and well-informed view of race relations in Australia, and for Indigenous children to feel valued, included and empowered.

At Empower To Teach, we think that exploring the notions of justice and injustice, how they are experienced in every-day life, and how restorative justice can play a positive healing role, is something well worth doing.

Teachers know their students are not strangers to injustice.

In our classrooms, in the school yard, when a child comes to us in distress, we see first-hand the wrongs that people will sometimes do to each other. Whether it’s psychological or physical bullying, slurs and insults, othering and ostracising, theft and even outright violence, we have seen and dealt with it all.

So, when it comes to exploring justice and injustice with students, experience at the personal level is a good place to start.

2. Starting with the personal

‘…This is the torment of our powerlessness.’

Uluru Statement from the Heart

Young people instinctively know what injustice is, how it disables and disempowers. They know what it is like to feel one is not being heard, believed or understood.

Possible classroom activities

Productive discussions can be had asking students:

Think back to a time when you were hurt by others; how did the world look to you after the act? (Alternatively, someone you’re close to who has been hurt and you’ve gone on the journey with them)

Were you/they listened to, were you/they believed?

What were the frustrations that you/they felt after the incident?

Was the wrong made up to you/them? What did it take for this to happen? Are you/they satisfied with how it all ended?

If the wrong hasn’t been made up, how are you/they feeling about words like justice, fairness, equality, acceptance?

An open class discussion can be an efficient way to work methodically through these points if the environment is safe and trust is there. Alternatively, your students’ responses can be collated, shared and discussed anonymously using whatever tools and approaches you are familiar with, or by using these free ‘sticky note’ apps:

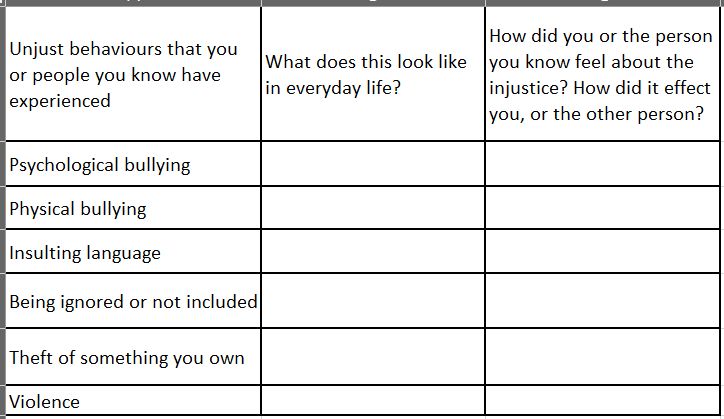

Another approach might be to use a table like the one below itemising the types of injustices people experience:

3. Extending student thinking

‘Makarrata…the coming together after a struggle…a process of agreement-making…and truth-telling’

Uluru Statement from the Heart

The victim of an injustice also experiences a sense of powerlessness. The innocent child feels they do not have the means by which to respond to the offence that either happened at school or has spilled into the school.

That’s when we intervene. That’s when we seek to restore justice in a way that cares for the one who has been wronged. We also seek to help the wrong doer identify healthier forms of behaviour - in a sense, to free the wrongdoer from their worst selves.

And fractured relationships must be healed or made workable - with the victim feeling that they have received justice - if things are to move forward.

At Empower To Teach, we know that many schools and teachers draw on the principles of restorative justice and adapt its practices to heal fractured relationships.

Possible classroom activities

We might ask students the following:

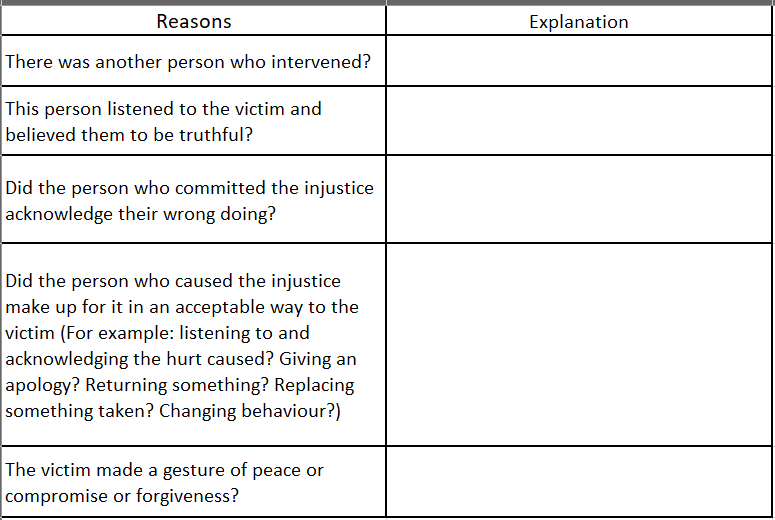

If the instance of injustice discussed above has been satisfactorily dealt with, to the victim’s satisfaction, was it because:

2. If the instance of injustice discussed above has not yet been satisfactorily dealt with, is it because:

The restoration of justice often requires the intervention of a third party that sits outside the conflict and calmly brings together all involved:

Some students will have themselves played this role restoring relationships amongst members of their peer group

Some students will have seen this mediation work happen within their families

Students will have seen teachers skillfully play this role

When can teachers bring up, and make fruitful use of these discussions in the classroom?

When analysing characters and themes in literary texts

In the study of war and conflict

When studying key players and movements in history

In Positive Education and Health and Human Development classes when the topic of conflict resolution is broached

Anytime when an injustice is known and negatively affects the well-being of the whole group

It’s never not a good time to work with students to reflect on injustice and what is required to restore justice.

4. Moving from the personal to the world around us

So, starting with the personal is one way to foster within children and adolescents an understanding of the importance of extending empathy and compassion beyond themselves.

However, making the transition from the personal to the wider world is a judgement the classroom teacher will make based on students’ age and context. It may not be appropriate or urgent to do so.

Nevertheless, the six behaviours given above that can result in people experiencing injustice can be applied to large groups within society.

Possible classroom activity

Depending on the context, the table below can be used.

It might be a good idea for teachers to widen the focus here and include alongside Indigenous people other groups who have experienced marginalisation and disadvantage. Other groups to bring into the discussion could include:

Refugees and asylum seekers

Religious minorities

Ethnic minorities

Again, an open class discussion methodically working through these points is an efficient way to go. Of course, the above apps can also be used.

5. Bringing it together

Let’s help our students understand that as we all share a common humanity no one is untouched by injustice, but everyone is lifted when justice is restored.

It’s been said that restorative justice is a way of dealing with the past. Therefore, whether something happened earlier in the day between individuals, or last month, or last century and even further back between whole groups of peoples and nations, broken relationships can be healed by the coming together of all involved, sharing the truth and finding agreement on how to proceed.

‘…empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country”

Uluru Statement from the Heart

A final word from Uncle Glenn:

Priest, Artist, Writer - Wiradjuri

The Statement from the Heart signed at Uluru in 2017 by 250 representatives of local communities is a powerful restorative justice document. It was written after an extensive cultural consultation with First People across Australia. It involved 12 consultations and some 1200 local people.

Its principles of Voice, Treaty, Truth and Makarratta reflect the process of restorative justice often used in schools and other places to address conflicts and issues. Like all such processes they take time and each element both stands alone and as constitutive of the whole.

It is not a new concept. It is the process our people used to resolve issues long before Western culture arrived here. It is part of the First People's commitment to wholeness and belonging, ensuring that issues did not fester and wreak destructive power over the community.

It is a concept that remains central to future reconciliation in this country.

To discover more, you can sign-up and download our teachers resources packages here.